I just learned that Robert Jay Lifton crossed over on September 4, 2025 – a few months ago. His books and work were a tremendous inspiration to me when I was in medical school and psychiatry residency. I was able to see him speak once, at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies annual meeting in New York City. I also interviewed him by phone 8/13/21, which can be found on The POV interview website that I run with my friend, Usha Akella.

I was particularly interested in his concepts of malignant normality and the witnessing professional. Based on his work, as a social psychiatrist, interviewing Nazi doctors, atomic bomb survivors in Japan, and working with Vietnam veterans, Lifton went on to become a role model as a medical activist – speaking out about war, nuclear weapons, climate change, and late in his life, about the dangers of Donald J. Trump’s words and actions. Quotes below are from our interview.

“I came to the idea of the witnessing professional in connection with a companion term of malignant normality. Malignant normality being the imposition on a society of a set of expectations that are highly destructive but are rendered ordinary and legal. Of course, the most grievous and extreme example of malignant normality is in connection with my work on Nazi doctors. In that sense, the German physician at the ramp in Auschwitz and other camps, sending Jews and others to their deaths was functioning in a kind of malignant normality. That is what he was supposed to do. That was his job, so to speak.

Within malignant normality we professionals have the capacity for exposing it, identifying it, and combating it, and that is the development or evolution of the witnessing professional. He or she is witness to the malignance of the claimed normality and not diminishing one’s professional knowledge but actually calling it forth as a means of creating one’s particular witness.”

From his study of extreme socio-psychological situations, Lifton cautions us about the dangers of gradually growing to accept what is not normal – what he calls malignant normality. And he offers an antidote to malignant normality through the role of witnessing professionals whose ethics require us to speak up and speak out against social ills in the world – such as the climate crisis or American fascism and totalitarianism.

Lifton wrote the original foreword, “Our Witness to Malignant Normality,” for The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 37 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President – Updated and Expanded with New Essays. Bandy X. Lee, psychiatrist and author of Violence: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Causes, Consequences, and Cures, brought together a group of civic-minded mental health professionals in 2017 for a conference at Yale, which was later published as The Dangerous Case, a first edition with 27 professionals, and later 37 professionals. Another trauma expert (another influence on my education in trauma and psychiatiry), Judith L. Herman, co-wrote the prologue with Bandy X. Lee, “Professions and Politics.”

Lifton’s concept of the witnessing professional provides a view of professionalism which moves beyond the narrow confines of the four walls of the consulting room to include the a responsibility to the larger ecological, social, and political world.

“I became interested in the history of what we now call professionalism and the professions and, as you may know, it begins with profession as a profession of faith, of religious faith or commitment to a religious order. Over time, especially as we developed and moved into more of modern society, the idea of a profession became more associated with skills and increasingly technical skills. So, the idea of the professional or the profession became, what I would call technized, and the moral element of it was, in a sense, neglected or denied. In its most extreme form, the technized professional is a kind of hired gun for anybody who will pay him or her for professional knowledge.

So, the witnessing professional, then, is a return to the inclusion of an ethical dimension in professional work. If you or I carry out some form of psychiatric or medical healing―that can be seen quite easily as a moral or ethical act. We shouldn’t lose the ethical dimension of being a professional. It is true that sometimes, as a professional, we have to step back and not experience fully another’s pain, or even the pain that we cause others, such as with a surgeon making a delicate operation or even a psychiatrist taking care of a very disturbed patient. But, at the same time we need to maintain, within the concept of the professional, that ethical or moral dimension and our own openness to some of that pain.”

Lifton’s work has inspired my own writing on the idea of medical activism as a professional, ethical responsibility, as well as my series of essays entitled Words Create Worlds.

Now, more than ever, we need to heed Lifton’s warnings about the risks of accepting malignant normality and we all need to embrace the idea of the witnessing professional.

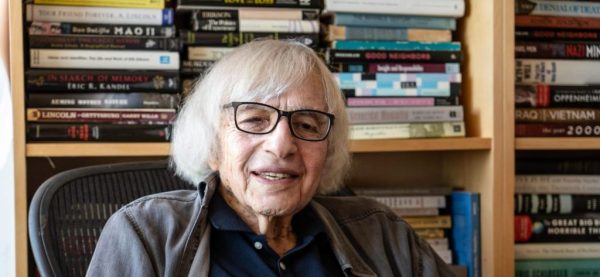

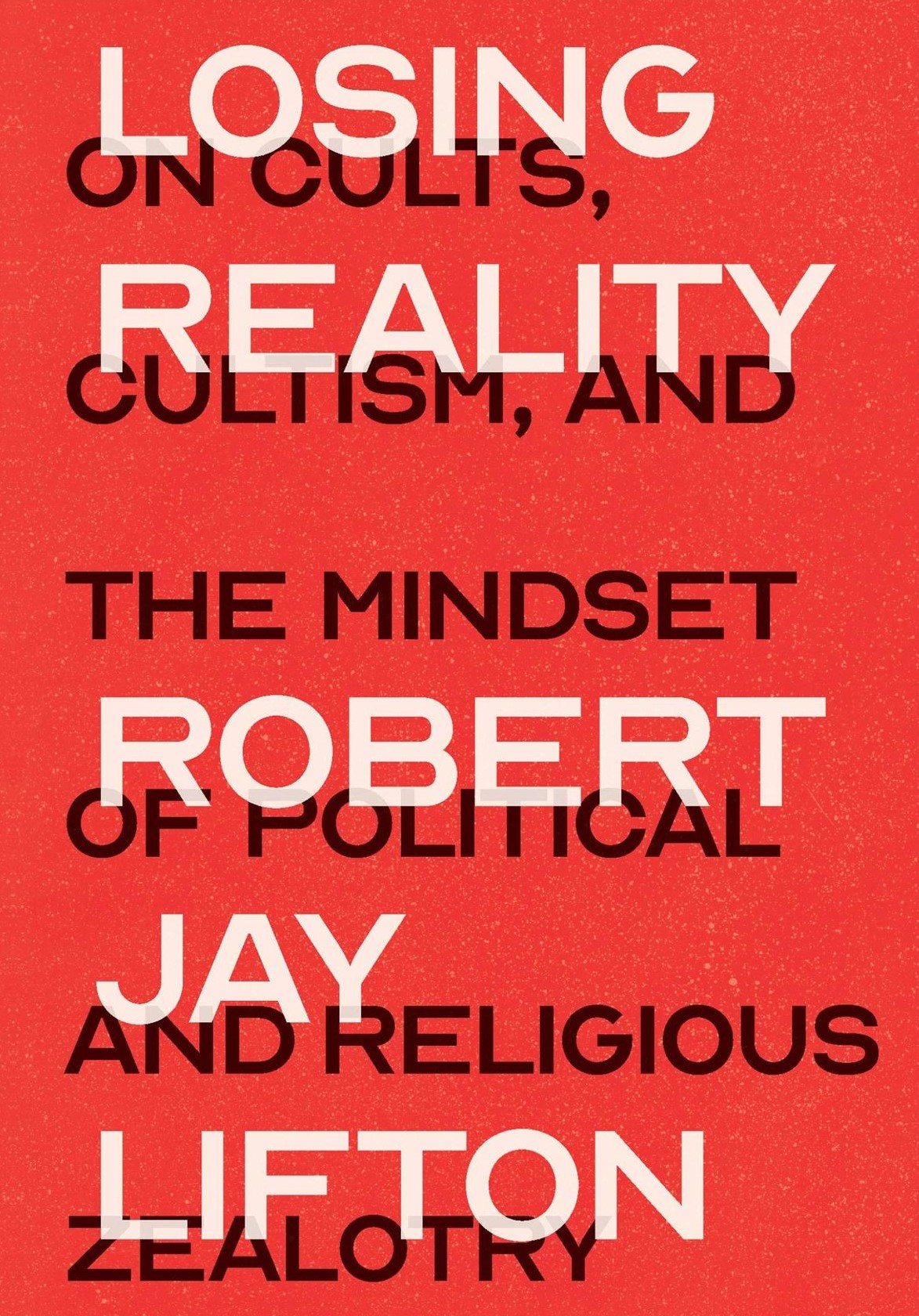

For excellent overviews of his life’s work, see books:

Losing Reality: On Cults, Cultism, and the Mindset of Political and Religious Zealotry

Surviving Our Catastrophes: Resilience and Renewal from Hiroshima to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Witness to an Extreme Century: A Memoir

My 8/13/21 interview with can be found on The POV interview website, the-pov.com.