I have not posted anything on the site for a few months as I have been in the process of moving back from New Zealand to the United States. An international move takes a lot of energy and planning and I am just starting to get settled into our new home in Seattle. Although we have visited Seattle many times, this is the first time we are living here, so it is a sort of home-coming to the US, but it is also a move to a new city. We are living in a one bedroom apartment for the time being, our belongings have arrived, but will be in storage until such time as we buy a house, so this is an extended transitional stage. I have been reflecting on a number of larger life topics during this transition and during this particular stage in my life. I think the “largeness” of these topics warrants another installment in the Coniunctionis column that I started around 2000. I borrowed this term from Jung’s major work on alchemy and personal/spiritual transformation, Mysterium Coniunctionis. Chalquist defines Mysterium Coniunctionis as “the final alchemical synthesis (for Jung, of ego and unconscious, matter and spirit, male and female) that brings forth the Philosopher’s Stone (the Self). Its highest aspect, as for alchemist Gerard Dorn, was the unus mundus, a unification of the Stone with body, soul, and spirit,” (Glossary of Jungian Terms). Jung’s study of alchemy is related to his study of Gnosticism, both of which served to link his inner experiences and visions of The Red Book with historical traditions of mysticism and divine revelation. He saw the Gnostics and the alchemists as carrying on the tradition of inner experience of the divine, a form of mysticism. This work of transformation required inner work as well as outer work, in a truly holistic manner. Jung wrote that the “alchemists thought that the opus demanded not only laboratory work, the reading of books, meditation, and patience, but also love,” (The Practice of Psychotherapy, CW 16). Thus, in my Coniunctionis column, I investigate transformation from a wide-ranging variety of sources. In this installment, I will examine the framework of the hero’s journey for my own situation, for returning war veterans, in literature and movies, and in the work of psychiatrist Carl Jung and science fiction writer Philip K. Dick.

SEPARATION & RETURN

The theme for this column is “separation and return,” and I borrow this concept from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell elucidated a common underlying theme that can be found in mythology, religion, literature and in people’s lives. Campbell was influenced by Jung’s ideas (particularly archetypes and the collective unconscious) and applied them to the field of mythology. He influenced popular culture (George Lucas admits that he drew on Campbell’s ideas for the plot of “Star Wars”). The map of the journey can be briefly summarized as a movement from the everyday world, to a series of struggles crossing a threshold into another world and then crossing the threshold back to everyday life. different variations of this journey can be seen in mythology and religious stories, as well as in the lives of artists and visionaries. What particularly interests me at this time is how this framework applies to my own situation of having left the US to live in New Zealand for over 3 years and to now be in the process of returning. I have also been pondering how this framework might be useful in helping veterans returning home after deployment (as my job I am starting next week will be with the VA).

Here is a visual diagram of the hero’s journey from Wikipedia , (further reading under the “Monomyth” heading):

Campbell gives an overview of the journey as follows:

The mythological hero, setting forth from his commonday hut or castle, is lured, carried away, or else voluntarily proceeds, to the threshold of adventure. There he encounters a shadow presence that guards that passage. The hero may defeat or conciliate this power and go alive into the kingdom of the dark (brother-battle, dragon-battle; offering, charm), or be slain by the opponent and descend in death (dismemberment, crucifixion). Beyond the threshold, then, the hero journeys through a world of unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces, some of which severely threaten him (tests), some of which give magical aid (helpers). When he arrives at the nadir of the mythological round, he undergoes a supreme ordeal and gains his reward. The triumph may be represented as the hero’s sexual union with the goddess-mother of the world (sacred marriage), his recognition by the father-creator (father atonement), his own divinisation (apotheosis), or again–if the powers have remained unfriendly to him–his theft of the boon he came to gain (bride-theft, fire-theft); intrinsically it is an expansion of consciousness and therewith of being (illumination, transfiguration, freedom). The final work is that of the return. If the powers have blessed the hero, he now sets forth under their protection (emissary); if not, he flees and is pursued (transformation flight, obstacle flight). At the return threshold the transcendental powers must remain behind; the hero re-emerges from the kingdom of dread (return, resurrection). The boon that he brings restores the world (elixir), (Campbell, 245-246).

Campbell describes hero themes of warrior, lover, emperor, world redeemer, and saint. We can apply this framework of the hero’s journey to these external journeys, as well as to the internal journeys of artists and creatives (this would of course apply to Carl Jung and Philip K. Dick’s experiences as well, which will be the focus of my next book). While action-oriented, downward part of the cycle is the one that is most often focused on in movies, the return is just as trying and it is this part of the journey that separates the successful heroes journey from the tragic heroes journey. (The tragic journey is well-exemplified by rock and roll heroes like Ian Curtis or Curt Cobain, who achieved the boon, but were destroyed by it and were unable to integrate it back into a live-able and sustainable life). It is precisely this return that I now find myself in and which draws my interest and enthusiasm. While I don’t mean to aggrandize my own experience of living in another English-speaking country and returning back to the US, I do believe that there are some universal themes of the hero’s journey that apply to cross-cultural repatriation and to returning war veterans, as well as to works of literature.

For instance in Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings, Frodo can be seen as having difficulties fitting back into society after his wounds and experiences. Sam has an easier reintegration and creates a new family. Frodo continues to suffer from physical and emotional pain from his wound and from his experience of proximity to evil. Compared to Sam, Frodo always remains somewhat apart from the society that he gave so much to save – an obvious parallel with returning war veterans. This example from literature shows that even when the returning hero has quite literally “saved the world,” the return can still be problematic and for some is never complete. It could be said that with Frodo’s return, he is “in but not of” the society of the Shire. He remains partly outside of it. In choosing this language from the Bible, I purposefully invoke the themes of mysticism as another example of journey and return. For Carl Jung and Philip K. Dick, after their inner journeys, the rest of their lives were focused on translating and linking back to historical and contemporary society their inner experiences with a larger purpose and meaning for others. Within Jung’s Red Book can be seen the glimmering of his mature works on Gnosticism and alchemy. Philip K. Dick’s 8,000 page Exegesis shows his persistent and never-ending attempts to understand his intense and overwhelming experiences of February/March 1974. Also worth mentioning is Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf which works on the theme of how those “outside” of society actually nourish the cultural life of those “inside” society.

THE LIMINAL BOUNDARY

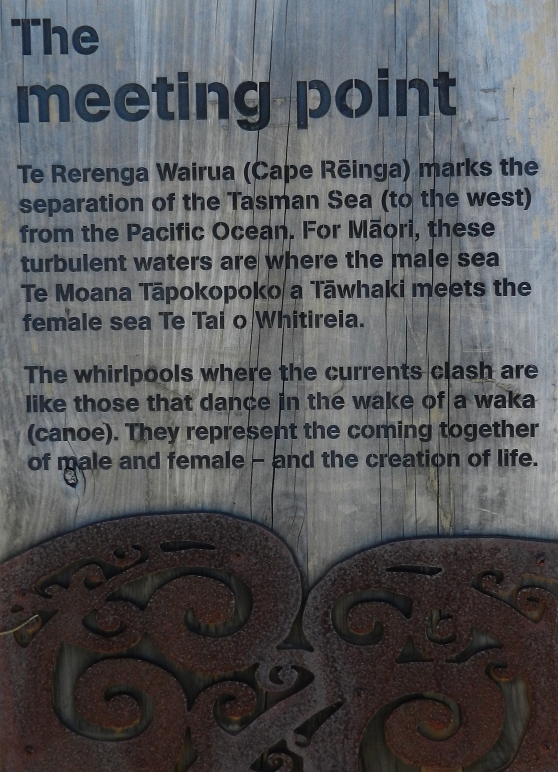

Let us turn to the horizontal line between the known/unknown in the diagram of the hero’s journey, above. This threshold can be considered to separate the mundane from the sacred, the worldly from the other-worldly, and consciousness from unconsciousness. Those who have studied initiation rituals and transformation sometimes speak of liminality. For instance, Arnold van Gennep’s 1908 book, Rites of Passage, examines pre-liminal, liminal, and post-liminal initiation rites. This roughly corresponds to separation, initiation, return. The focus on managing this liminal boundary can be seen in concepts like tapu and noa in Māori culture (see Coniunctionis.17) as well as well as societal structures that manage individuals instincts and enthusiasms.

CULTURE & RELIGION’S BOUNDARIES AROUND SEXUALITY & SPIRITUALITY

This is an interesting parallel between Freud and Jung in regard to culture. Freud’s views on culture are that the role of culture is to inhibit and channel the libido (sexuality) of individuals. Whereas Jung’s view of libido had more to do with spiritual and mystical energies (of which sexuality was one expression). Both Freud and Jung were ambivalent toward society and culture, on the one hand seeing it as a limitation of the individual, while on the other hand seeing it as a protective element against the dangers of instinctual drives and eruptions of the archetypes of the collective unconscious, respectively. This also is the tension between religion (which seeks to structure and define “legitimate” spiritual experience) and mysticism (which is the direct access of spiritual experience by the individual that is unmediated by social or religious structures).

WHICH SIDE OF THE BOUNDARY IS “THE REAL WORLD?”

The liminal boundary separates the ordinary world from the non-ordinary world. From the perspective of society, the ordinary world is reality. From the perspective of poets, mystics, it is the liminal world that is Reality, where one feels really alive, connected with the cosmos, in union with the divine. Many Eastern philosophies, such as Hinduism and Buddhism speak of the ordinary world as being a veil of illusion over the Real world. Western Gnosticism, similarly speaks of the ordinary world as an illusion or delusion that leads one away from the true world of Spirit. The Matrix trilogy played with these ideas from a technological rather than a spiritual and metaphysical perspective. The resurrection of these concepts in modern form attests to a large part of the popularity of that trilogy, above and beyond the action and visual effects of the movies. Henry Corbin’s work on Persian Sufism and mysticism also picks up this theme that the ordinary world is a projection or creation of a “more real” spiritual world (this is an extreme simplification of his prodigious work which merits a Coniunctionis column of its own). And lastly, I’ll mention Amit Goswami’s work in The Quantum Doctor and The Quantum Activist in which he argues (from a Quantum physics point of view that intersects with Hindu philosophy) that consciousness is the primary reality and matter a secondary manifestation of consciousness.

THE DANGER AND THE ATTRACTION OF LIVING IN THE LIMINAL WORLD

The source of mana in indigenous Fijian culture is believed to reside in the “mana-box” (kato ni mana) buried in the depths of the ocean. Katz describes this in his book, The Straight Path: A Story of Healing and Transformation in Fiji, (p. 22), and he tells of how healers are called in dreams to dive down into the abyss in order to bring back the boon of mana to use for healing purposes for the community.

Why would anyone want to return from the liminal space of the unknown if it is the source of creative and spiritual inspiration, of mana, of transformative energy, and the boon of the hero’s journey? This is of course a very real dilemma, Jung recognized this, as do any cultures with a conception of the liminal threshold to the sacred. This potential energy is energy of transformation and that means destruction of old forms as well as creation of new forms. Human life, the stability of society, and the mental stability of the individual depend upon a balance of structured forms as well as an influx of transformative energy, as was discussed in Coniunctionis.17 regarding the Apollonian and Dionysian dialectic. As David Tacey writes in his recent book, The Darkening Spirit: Jung, Spirituality, Religion, Jung’s position fluctuated regarding the role of religious and societal boundaries and the individual’s quest. Jung respects the transformative power of the liminal realm (the archetypes of the collective unconscious) and saw that contact with this realm was inherently dangerous and could destroy the individual as well as be healing or transformative. Jung struggled with this personally in his life, and while ever a champion of the individual, he recognized that the individual’s continued existence is rooted in society. He wrote that “The opening up of the unconscious always means the outbreak of intense spiritual suffering: it is as when fertile fields are exposed by the bursting of a dam to a raging torrent,” (Jung, “Psychotherapists and the Clergy,” CW 10). Further, “The modern man must be proficient in the highest degree, for unless he can atone by creative ability for his break with tradition, he is merely disloyal to the past,” (Jung, “The Spiritual Problem of Modern Man”). This implies that there is a complex reciprocal relationship between the individual, the liminal unknown (the collective unconscious), and society. The individual must be willing to leave the safety and boundaries of society; then risk being overwhelmed by the liminal abyss (Mogenson describes any overwhelming, traumatic experience as being synonymous with “God,” see God is a Trauma: Vicarious Religion and Soul-making, this idea is similar to that of indigenous cultures view of the sacred as being both beneficial and dangerous, anything that is overwhelming is sacred and must be handled very carefully); and then must return to society, carrying something (having become someone) that is bigger than one’s previous place in society. The fact of the heroes transformation mid-journey is the fact that the same essence that is potentially transformative for society is the same essence which causes society to reject the transformed individual (recall Jerzy Kosinski’s myth of the “painted bird” who is attacked and killed by its flock because it is simply painted a different color).

The transformed individual simply does not fit back into the place/role in society which they left and yet to complete the hero’s journey, they must accomplish the return for their good as well as the good of society. Tacey writes, “The boon must be shared and brought into the community…spiritual experience is not complete until one finds a way back to others…We make the journey back not only for the sake of others, but for our own mental health as well,” (Tacey, 151).

This dilemma leaves several possibilities (Campbell explores many of these variations in The Hero With a Thousand Faces):

1) the prototypical, successful hero’s journey ends with a successful reintegration back into society in which the transformed individual is given/creates a new role in society and society appreciates this work;

2) the tragic hero’s journey in which the individual either dies, commits suicide, or returns but is not accepted;

3) the rejection of the return, the individual chooses not to return and rejects the original society (this could be madness, becoming a hermit, or for a veteran, perhaps re-enlisting);

4) the rejection of the boon, the hero tries to go back to who they were before their transformative journey;

5) or various combinations of these possibilities.

The work of a successful return has both inner (individual) and outer (collective) elements. What if the “boon” of the returning individual is not clear? What if the individual only recognizes that they have changed, that they are different, but does not see a path as to how this difference can be a boon or benefit to them or to society? What if society rejects what the hero brings back? For instance, Vietnam veterans were often viewed as villains rather than heroes. Society may just see the individual as changed and react to that without seeing how it can be of collective benefit. What if hero rejects his or her experience of transformation, and simply tries to fit back into their previous role in society (this is a common dilemma for those who experience trauma, that they reject the transformation as it seems only negative and they strive to recover their “lost” previous life and self). The inner work for the individual is to integrate the overwhelming, transformative experience. If this is not done, it will make the individual’s return much less likely to be successful. In many ways it is not realistic to expect that society as a whole will change to welcome transformed individuals with open arms. It is society’s goal to be conservative and to be cautionary about integrating individuals who are unpredictable. Jonathan Shay wrote, in his book Achilles in Vietnam, about the role that acting and drama had for returning war veterans. They were given a place in society that was respected, that helped them work through their transformation, and also transformed society in the process. That would be an ideal, that the structure of society would provide effective boundaries but still recognize the need for creative growth and transformation. Many earlier societies provided this type of balance to provide safety, community, belonging, as well as creative spiritual space for individual transformation. For instance, warriors preparing for battle or returning from battle in Māori culture were considered tapu and rituals would be used to render them noa.

MY RETURN

In closing, let us move away from the theme of returning war veterans, back to my more immediate concern of reintegrating back into the US after almost three and a half years in New Zealand. (Again, I hope it is clear to the reader that I am moving back and forth between related universal themes and not claiming my experience is that of a returning war veteran, a traumatized person, or a “hero”). The concept of “reverse-culture shock” speaks to this idea that a return home after living in another culture can have its own challenges. Picking up on the framework discussed in this column, leaving one’s culture and living in another culture transforms the individual. This transformation can be both positive and negative for the individual and it requires inner work in order to integrate new experience into the Self of the individual. For myself, I took 5 weeks off before starting work. I have spent time reconnecting to family, I’ve made two trips back to the Mid-west. I have also spent a lot of time on my own, reading, writing, thinking, walking, meditating. I have talked with others when appropriate; I recognize that my need and capacity to talk about New Zealand generally is greater than the listener’s capacity/interest to listen. It really helps that Mary Pat and I have both gone through the experience together of moving abroad and returning, however, every individual’s experience is different and even within the relationship there is the challenge of balancing and integrating each of our individual experiences of separation and return. I have turned to reading books like Corbin’s Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi. As somewhat of a parallel thinker to Jung, and a mystic scholar, Corbin has provided a spiritual framework that complements Campbell’s hero’s journey. I suppose to voluntarily leave one’s own home culture for a period of time, quite possibly presupposes a degree of alienation from the home culture in the first place. I know for me it did. Thus, I find myself in a situation in which I am reflecting how to integrate my time “down under” (the “underworld”) into my professional and personal life. This is occurring for me at the age of 46, which intersects with the larger mid-life transition (Jung’s work was very focused on the mid-life transition and in fact both for him as well as Philip K. Dick, their visionary experiences occurred at mid-life). The universal questions of any reflective person take on new meaning and urgency at this point in life, so I suppose I have a bit of a double whammy with my stage in life as well as with my return “home.”