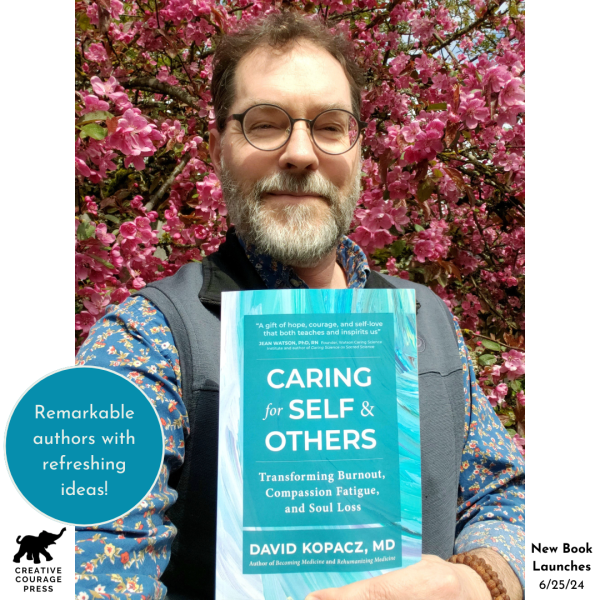

Caring for Self & Others: Transforming Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Soul Loss, Creative Courage Press (June 25, 2024).

I have been working on this book for ten years – the longest of any book I’ve written. In many ways it is a follow-up of Re-humanizing Medicine (2014) and yet it also is strongly influenced by my work over the past 10 years with Joseph Rael (Beautiful Painted Arrow). It brings together my work on physician and staff wellness in presentations and workshops, from my work Whole Health at the VA, and my work with The Doctor as a Humanist. Re-humanizing Medicine used a 9-dimensional model of the components of being fully human: body, emotions, mind, heart, creativity, intuition, spirituality, context, and time. In Caring for Self & Others, I’ve added the dimension of Becoming Caring: Caring for All, a kind of holistic leadership for self & others. Within each of the ten different dimensions of being fully human I have developed three different domains that end in an -ing (in honor of Joseph Rael’s emphasis on verb-ing in our conversations). I’ll now give a brief review of the journey of how this book has come into being.

After publishing Re-humanizing Medicine, I realized I needed to develop a set of practices to operationalize what I called the counter-curriculum. The counter-curriculum was a humanizing curriculum, a caring for self curriculum, which focused on how we do things, not just what we do in clinical settings. If our medical education and continuing medical education (CME) trains us to be good clinicians, the counter-curriculum trains us to be good human beings – thus I came to call this Continuing Human Education (CHE). In the age-old balance of being healers and technicians, I recognized that we have really given the education of ourselves as healers short shrift, and have almost exclusively focused on becoming technicians at the expense of our humanity. The loss of our role as healers and the loss of our human presence in medicine leads not only to impoverished clinical care (with patients feeling like they are being processed by protocols rather than cared for by human beings), but it also cut us off from the rejuvenating nature of the healing relationship which nourishes our own humanity as well as the humanity of our patients and clients. I realized that to care for others we must first care for ourselves and that in caring for ourselves we were developing the skills and aptitudes necessary to care for others.

In 2015 I was developing the idea of “Becoming a Whole Person to Treat a Whole Person,” which I presented in various forms at the Australasian Doctors’ Health Conference, and conferences of the Alliance of International Aromatherapists, and the Australasian Integrative Medicine Association.

In 2016, Joseph Rael and I published Walking the Medicine Wheel: Healing Trauma & PTSD. That year I deveoped presenations on Healing Circles, Pathways to Healing Moral Injury, and comparing the Medicine Wheel and the Hero’s Journey as pathways of initiation and healing – with presentations at the Mayo Clinic Humanities & Medicine Symposium, and various local settings. I developed a half-day workshop called “Caring for Self: Well-Being in the Workplace” that I gave for HopeWest hospice staff in Grand Junction, CO.

In 2017 I first started using the title of “Caring for Self & Others” in presentations, for instance at Western Sydney University in Australia. I continued developing ideas around Healing Circles and the Hero’s Journey, with presentations at the Australasian Doctors’ Health Conference and the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.

One of the dimensions of being fully human from Re-humanizing Medicine was spirituality and I had a sub-section on mysticism and medicine. My work with Joseph Rael, which has resulted in the publication of four books thus far, has allowed an in-depth exploration of the role of spirituality in healing. Our 2020 publication of Becoming Medicine: Pathways of Initiation into a Living Spirituality was a blending of Joseph Rael’s teachings within a framework of initiation, a review of healing through the lives and writings of visionaries, mystics, and shamans, and a survey of the perrenial philosophy of timeless healing wisdom. My subsequent training as an iRest certified teacher (a Western adaptation of yoga nidra from Kashmiri Shaivism by psychologist Richard Miller) and as a certified yoga teacher (CYT 200), has allowed me to study and explore nondualistic states – which I feel are foundational to breaking down the barriers between self and other – a kind of nondual medicine, as I call it in Caring for Self & Others.

As I have been working with burnout for myself and in staff and clinicians, I started to realize that there were many terms for health care worker suffering, not just burnout, but compassion fatigue, secondary and vicarious traumatization, PTSD, demoralization, moral injury, and even suicide could be an outcome of the burden of caring for others. I have come to use the term the costs of caring to encompass all these different dimensions of staff and clinician suffering. My good friend Greg Serpa and I published a chapter on “Clinician Resilience” in the Integrative Medicine, 5th edition textbook and I started to bring together a number of ideas I had been working on around burnout, moral injury, and the costs of caring, and even the idea of soul loss.

Soul loss is often considered one of the causes of illness in shamanic and indigenous traditions, such as in the work of Joseph Rael. It also has a resonance with the Western traditions that psychiatry and psychotherapy grow out of. The etymology of the word “psychiatry” comes from the Greek words psyche + iatros, soul healer. The Swiss psychiatrist, Carl Jung, frequently wrote of the psyche and also of the soul in his work as a healer and psychotherapist. The more recent, modern tradition of neglects the idea of the a vital essence of a person – yet there is a practical utility in addressing burnout as “soul loss.” In doctors and health care workers, as well as in teachers, and business, burnout is such a serious issue. We talk about burnout, but what is it that burns out? The soul is one answer – not necessarily in a metaphysical or religious sense, although it could be understood that way, but in a metaphorical and evocative way of describing what burnout and compassion fatigue feel like – that one has lost some core aspect of one’s being – a loss of soul. I gave presentations on burnout and soul loss at the Doctor as a Humanist’s on-line international conference, New Realities in the Times of COVID-19 (2020), University of Washington Psychiatry Grand Rounds (2021), and Seattle University’s Giving Voice to Experience Conference (2022).

A key idea in Caring for Self & Others is that suffering can be transformed – this is what healing is all about and this is the primary skill that a healer has, how to transform suffering. Our work as healers, doctors, technicians involves exposure to suffering, therefore we cannot eliminate suffering from our work as the very definition of our work is to engage with suffering. We can minimize the amount of collateral suffering that we experience from working in systems that do not support the full human being of clinicians and staff – that is the moral injury piece that we need to address. However, I think that burnout is inevitable when we are people who work with people, particularly people who work with suffering people. In my conversations during the pandemic, Lucy Houghton and I have been developing the idea of post-burnout growth, which is analogous to post-traumatic growth, in which we use suffering as a stimulus to personal and professional growth. Post-burnout growth captures the idea that burnout is not to be feared, but rather respected as a predictable occupational hazard – just like a firefighter working with fires is sooner or later going to get burned.

The story of Chenrezig as a wounded healer captures this idea of post-burnout growth perfectly. Chenrezig vowed to alleviate all suffering in the world – which is not dissimilar to our own vows, spoken or unspoken, to heal others. If he was not successful in this vow, he pledged that he would shatter into a thousand pieces – a state akin to burnout, compassion fatigue, and soul loss, where we feel injured as a result of our caring. This is, in fact, is what happened – Chenrezig worked diligently, healing many, yet there was still more suffering than he could address and he shattered into a thousand pieces. This is where the story ends for so many health care workers and educators who become embittered, cynical, and maybe even leave their profession. But in the story of Chenrezig, there is a ritual elder, Avalokiteśvara, who sees Chenrezig’s suffering from addressing others suffering. Avalokiteśvara puts Chenrezig back together – not simply as he was before (this is my problem with the way resilience is often used in health care – as a way of going back to the past, or avoiding suffering), but rather as having a thousand eyes to better see suffering and a thousand arms to better touch suffering. Chenrezig becomes more capable of seeing and touching suffering – through post-burnout growth.

This book, Caring for Self & Others: Transforming Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Soul Loss, has grown over the last ten years and I am grateful to all the above mentioned organizations. The book and I have also been shaped by numerous conversations with friends and colleagues and I would particularly like to thank Laura Merrit, Shelly Francis (Creative Courage Press), Joseph Rael (Beautiful Painted Arrow), Steve Hunt, Jonathan McFarland, Usha Akella (The POV), J. Greg Serpa, Tulika Singh, Chris Smith, Lucy Houghton, Transformational Arts Network and their Power of Words conference, Gretchen Miller (and the editorial staff at the CLOSLER blog), and so, so, so many others. There truly is no self without others.