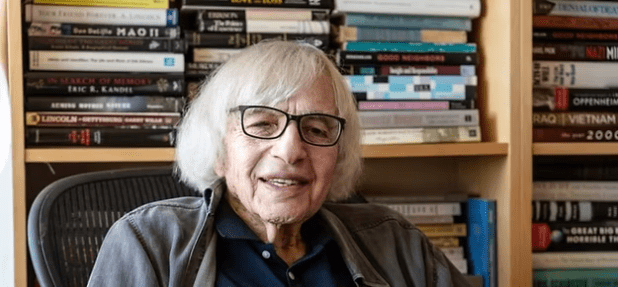

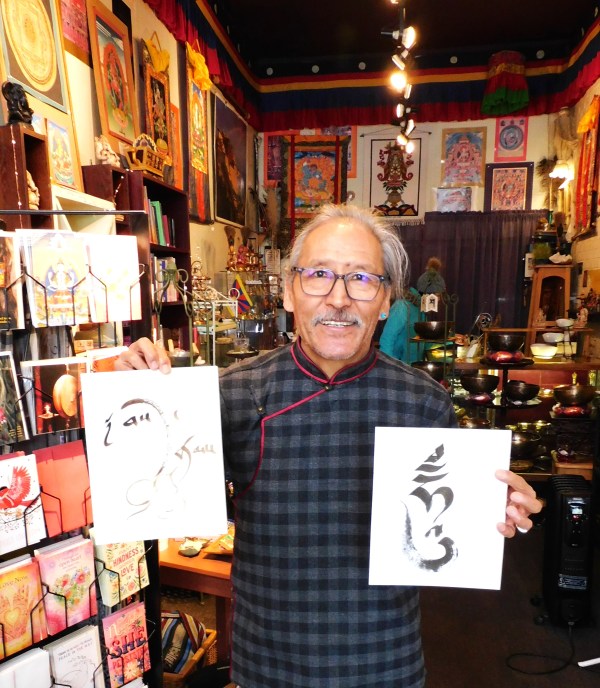

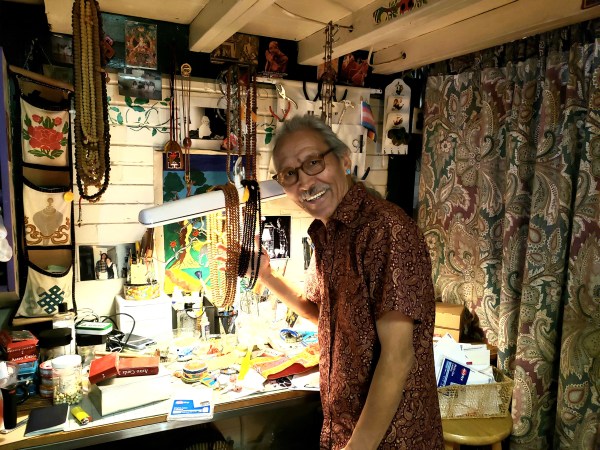

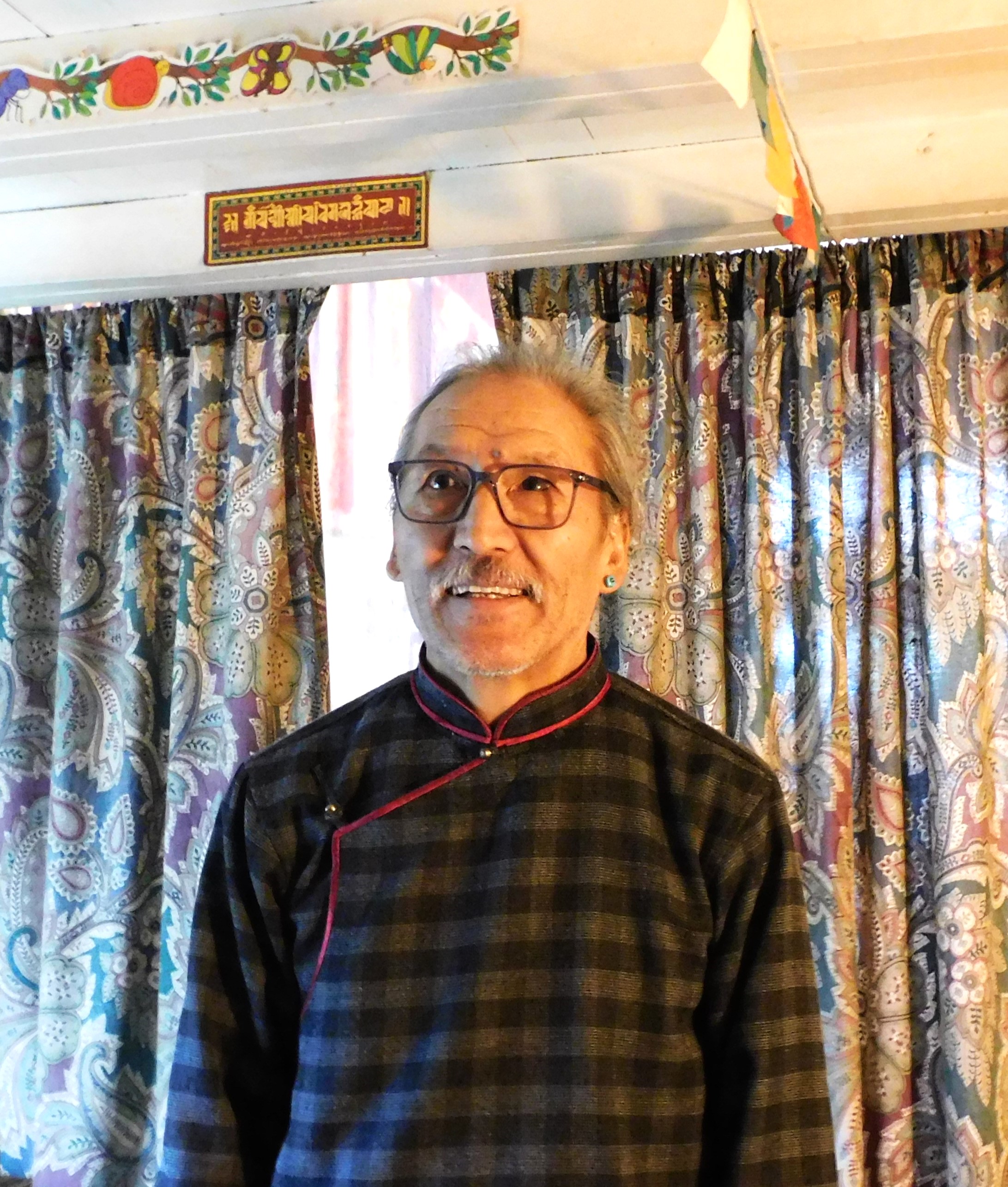

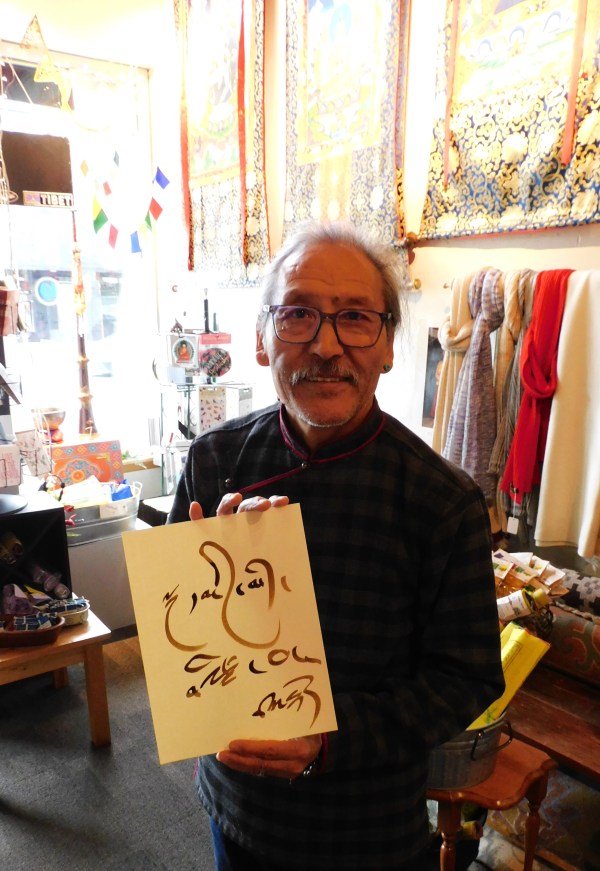

Rigdzin is the proprieter of Pema Kharpo, a shop selling imported Tibetan and Asian good, in the Greenwood neighborhood of Seattle. This was my go to place when I was looking for gifts for others, or a mala for myself. The place is good medicine. Rigdzin would often give me something for health or protection if I was feeling under the weather or traveling. We moved away from Seattle to Madison, Wisconsin in 2025 and I miss my conversations with Rigdzin, but I am finally getting this interview we did in 2024 posted! Rigdzin’s life story is so fascinating, born in Tibet, raised in exile in Dharamshala, meeting with the Dalai Lama on his visits to the Tibetan school, traveling to the US, working in restaurants and starting an import business on the side, serving as an interpreter for Tibetan monks on tours of the US, and now running Pema Kharpo and helping people connect to Tibetan spirituality. We will intersperse his calligraphy art throughout the interview.

David R. Kopacz: As I have spoken with you over the years I’ve been in Seattle, it seems you’ve had many roles in your life. Could you start at the beginning and tell me a little about your childhood and your time growing up in Tibet and then in exile in India after the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1959?

TIBET TO DHARAMSHALA

Rigdzin: I was one of those who were forced from their country and forced to live in another country. This is part of my role and life starting with unfairness—the opposite of peace. My parents went to India when I was two. So, I experienced, for example, living in a tent, as a concentration camp, so to say, but under the great open heart from India, at that time. We didn’t have any other countries’ support. Only India acknowledged that Dalai Lama can come in exile to Dharmshala. My role was like a child who was victimized by war and extreme poverty.

At a very young age, I was exposed to many, many different situations. I speak many languages, that’s one advantage. Another thing, I also really understand others’ pain. And the greatest blessing was the Dalai Lama’s teachings and Buddhism. From the very beginning, Dali Lama has taught about compassion, all the time, compassion. In Tibetan, this is nying-je. The literal word, nying means “heart,” je means “mighty.” Our heart is mighty, because you can understand others’ pain and see that anger and hatred causes so much suffering. The entire philosophy of Dalai Lama is always putting the other as more important than you. That is the philosophy I was brought up with.

DRK: So, you say that even though there were hardships of being in exile, and being a child of war, and being in extreme poverty, there were things that you saw as gifts like learning many languages and being able to see others’ suffering.

Rigdzin: Also, it was because of His Holiness Dalai Lama’s gentleness and love and his unwavering non-violence that actually gave us more strength, because the truth is greater than the force of hatred or bullying.

Rigdzin: Yes. I sometimes jokingly call my parents, “Dalai heads.” You know, you have a “dead head,” right? Who follows around the band the Grateful Dead? So, I remember my parents like that, following around the Dalai Lama wherever he went or wherever he sent them.

My father was a businessman. He had donkeys and ponies and horses and yaks. He would bring things from Tibet, and then he would bring back things from India. See, he already knew the route to India. So, when he escaped the Chinese invasion, sometimes we were one day apart from His Holiness Dalai Lama and sometimes one week apart on the journey to India. So, His Holiness first went to Arunachal Pradesh and we were already there.

I remember, as a child, since I was maybe three years old, I stayed in a tent. So even today, sometimes my wife takes me camping. When the weather is bad, I get nervous. Because for me, it is no fun living in a tent, ha ha! Especially when we had a tent that was Indian military surplus—they don’t have a floor!

Dali Lama left Tibet on March 17, 1959, after sometime he arrived in Dharamshala in April, 1960. My parents were the first ones who built the Dalai Lama’s new residence. And after they built that, our group was sent to different South India locations, because His Holiness’ whole idea was the future of Tibet.

All the kids were given some form of school, hostel school, boarding school, so that parents can go and make a living and the kids can learn Tibetan. My parents followed everywhere His Holiness Dalai Lama went or directed. They were 100% dedicated to His Holiness. They were unwavering, trusting the guidance of His Holiness Dalai Lama, for the good of their kids and themselves, as well as the people still inside Tibet who didn’t have a voice.

DRK: So, His Holiness was thinking of the future of Tibet and your future.

Rigdzin: Yes, yes, yes, yes. 100%.

THE DALAI LAMA’S TEACHINGS FOR CHILDREN

DRK: You’ve told me you were able to have audiences with His Holiness. Could you say more about what those meetings were like?

Rigdzin: See, after we moved to Dharamshala, I look back and think that was one of the most fortunate things that happened, because we got to see His Holiness Dalai Lama every other week. And we were all kids, but sometimes we were fifty, and sometimes we were two hundred. We would go to see His Holiness in his first residence, which was, actually, an old British summer house. I still remember, that his windows were broken, the glass was broken. So, we flattened American aid or Western aid, oil, cooking oil cans. They come in twenty-five gallon cans, the square ones. So, after the oil is done, we cut them, flatten them, and put a color on them. So, we made windows out of the metal cans. And His Holiness, maybe at that time was twenty-seven or twenty-eight years old

We were kids from maybe five to eleven years old. We all lined up and were excited to see His Holiness and he gave us advice. I still remember his advice at the time, according to our age and capacity, he said “I want you guys to be like a flower in the wild, not like in a manmade garden that can easily whither each season.”

At that time we didn’t know much about sanitation. We didn’t have hot water, no towel, very little, maybe one towel for ten kids. So, he said, “If you wash your face nicely, if you wipe your nose good, that also will help for Tibet, because people will say, ‘Look at that clean, smiling face, that kid is a Tibetan.’” I never forgot that was something that I could do. And always he told us we are fortunate and to be proud, because we are the children of compassion, tolerance, and good manners. Those are the things he liked to talk about. Then he always said, “Take care of each other.” Basically, encouraging compassion to everybody, even to the insects. As kids we grew up with those words and ideas which are really the blessings!

DRK: It sounds like he inspired you to think of yourself almost like an ambassador or emissary for Tibet. Anything else about those years and the experience of seeing the Dalai Lama?

Rigdzin: Yes, from the beginning, He saw each one of us having a profound responsibility for the future of Tibet. Nowadays, we are getting a deeper understanding of his vision, basically, perseverance of the message of truth and compassion, and that we are all interdependent. If we inflict harm to others, it has no end, it only gets worse. Our greater responsibility is the understanding that everyone equally wants happiness, but out of their own shortcomings, they inflict bullying and harming on others. But, actually, everyone is also exactly like me—who wants to be happy, who wants to be respected. So, I understand now the bigger and deeper meaning of why he has always taught non-violence. At that time, we were just kids, right? We just wanted to be mad with China, but His Holiness always says peace is the only possibility.

DRK: How did you end up coming to the United States?

COMING TO THE UNITED STATES

Rigdzin: I met a gentleman on an Indian street; I was selling clothes. I called it my Pema Kharpo [shop] on the street! Ha ha ha! I didn’t know in the future I would own an actual shop. Then I met this wonderful, tall, well-built Westerner, but wearing completely, torn clothes—he looked like a hippie. He looked very strong and he had a lot of cameras. He sat next to me, and he talked to me, because I was trying to read the newspaper. This happened to be an English newspaper. I didn’t know how to read very well. It was more like I wanted to have the image of reading, ha ha ha! He said, “Do you read English?” and then we talked and he said, “You are pretty good. Do you want to go to school?” I said, “I have no money.” “So you want to go to college?” “Yeah!” Then he said, “I will pay for your college fee.” So that’s how it happened. And he asked, “How much it will cost.” And I said, “10,000 rupees,” which was a lot of money at that time. $1 was about eleven rupees. Right now, it is 83 rupees for a dollar. So, he really gave me cash, ₹10,000.

So, I went to New Delhi, and I joined vocational college. And then, many years later, I also got a part-time job in a restaurant. And then two women from Olympia, Washington came in the restaurant looking for someone and asked me, “Do you know Rigdizin?” “Yeah,” I say, “I’m Rigdzin! And then they say, “We’re Chris’ friends.” And then I realized that he sent them to me because I could show them around. So, then I helped these two ladies as a guide. Then they asked me if I wanted to come to America and see what America looked like. They were very curious because one of the ladies said that she remembered ten lifetimes of her past life. And she describes scenery and regions in India and so we go—and they are really there! She said her family thinks she’s crazy. But that’s not crazy for me. So, that’s how we become friends. They invited me to come to see America. So, I came first to Olympia, Washington, and I liked it. Then I went back to India, to bring back more goods. I was lucky to get a visa, a business visa, legally. So, within one year, I could come and go. I went back to India and then I came back to the US and then stayed right here in Seattle.

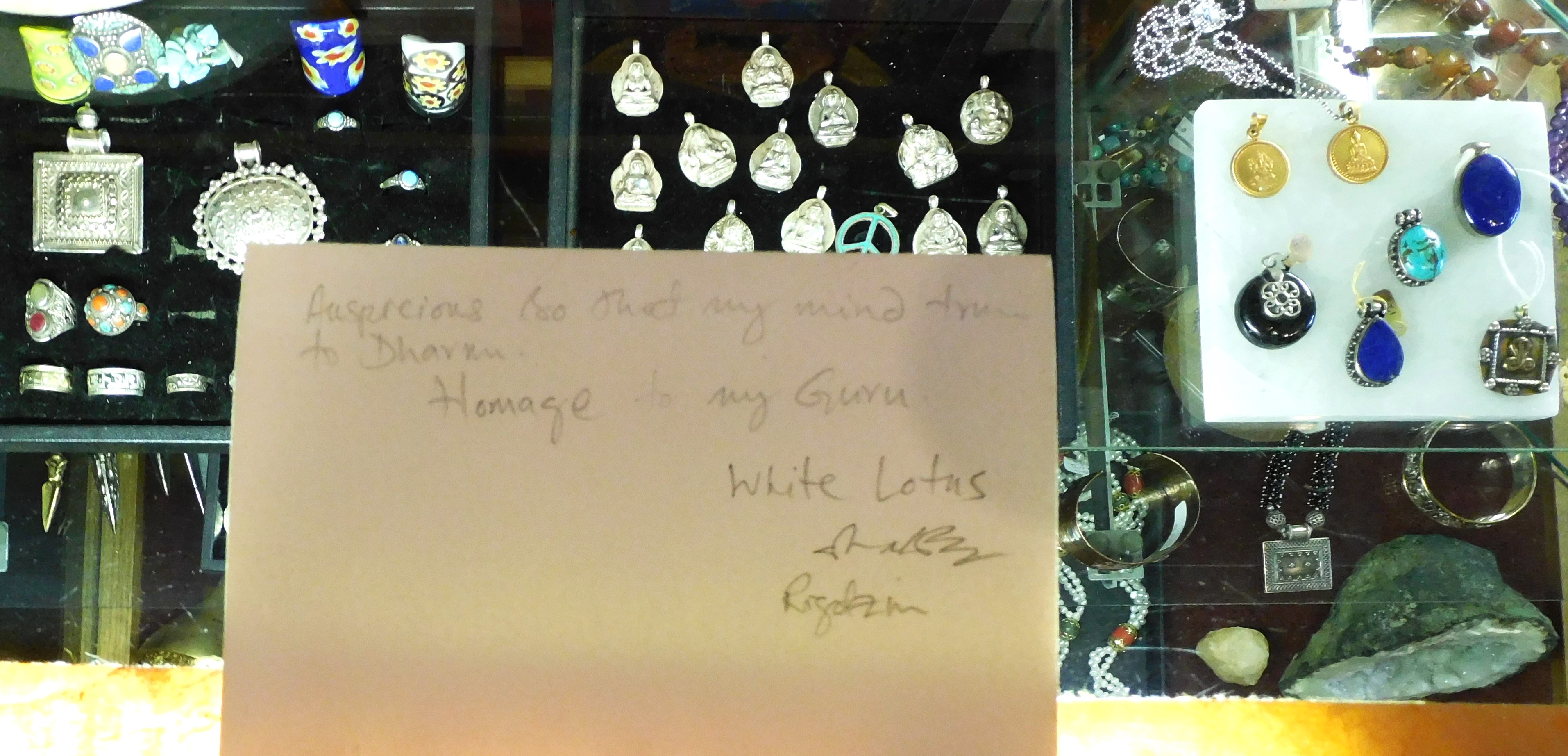

PEMA KHARPO: WHITE LOTUS

DRK: What did you do in the States then? Did you continue your shop, Pema Kharpo?

Rigdzin: Slowly, slowly, I started to bring my children here. For a few years, I asked for political asylum and then I immediately got a work permit. I worked some but mostly I explored America. People asked me to come here, come there, and I just went. And this is when I learned not only the language, but how people eat, right? How people fight. How do you use the bathroom. What is your culture and all of that. Then I picked up English very fast. I went to community college to brush up my English. But mostly I worked in a restaurant early on.

Then, the first time I went back to India to see my brothers and sisters, I had a credit card. Always, in the back of my mind, I wanted to do something for my community. So, when I had the credit card, I bought 100 rugs from our village. The Women’s Association, something like that we called it, through handicraft, made handmade carpets. Then in Olympia, I worked full-time as a cook. But every other weekend, sometimes, I would throw a small party and sell rugs out of my friend’s apartment. That’s how I started Pema Kharpo! Ha ha ha!

DRK: What does Pema Kharpo mean?

Rigdzin: White Lotus.

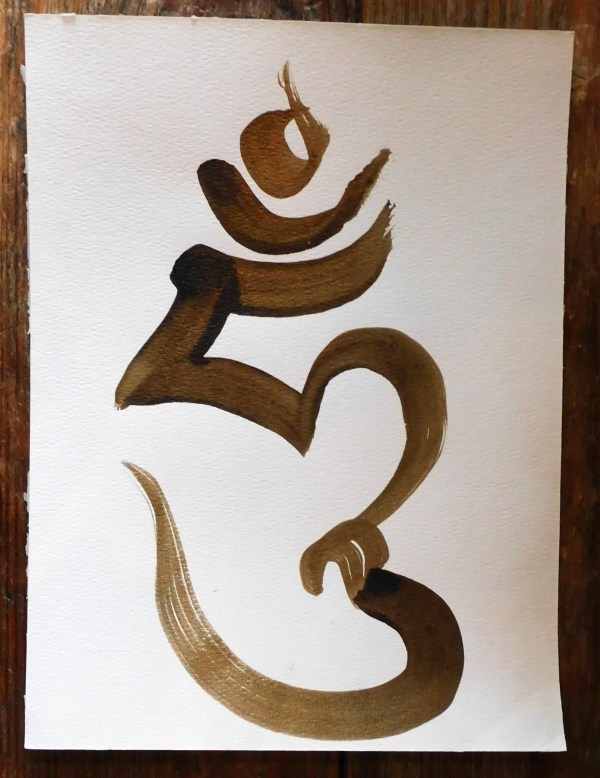

This is not just a flower. It has a lot to do with the Buddhist philosophy. The lotus grows from muddy water, but it does not carry muddiness, it is pure. So, we are all living beings born out of father and mother’s activity and desire. But each individual mind is uncontaminated and always has the possibility of complete awakening or freedom. Just like the lotus is growing muddy water—it is pure, it doesn’t carry that muddiness. My wife, when we first started the business, asked my brother, “Please give us some the Tibetan names of some flowers for the name of the business.” Then my brother said, “Pema Kharpo” So, yeah that’s perfect, ha ha ha! If you see images of the Buddha, they all sit on moon disc and lotus petal.

DRK: So, the shop started as a way to help people back home by selling their goods?

Rigdzin: Yes! This gives me a real joy and platform to express my art and my culture. Nowadays, I’ve been here 28 years, I have a lot of repeat customers. A lot of times, I get people who will ask me more questions than they buy. But I’m never unhappy about and like you said before, I have a responsibility even though I don’t know that much. But as a Tibetan, His Holiness said, “You are representing Tibet.” So, I try my best. When people have a question about Tibet, the diaspora, and Buddhism, I definitely have a little bit more insight than others who haven’t been through what I have been through. So, it gives me joy!

DRK: So, you’re a businessman. But you’re also—I suppose a businessman is a conduit of bringing something from one place to another place—but you’re also a knowledge man. You bringing knowledge from one place to another?

SERVING AS AN INTERPRETER OF THE DHARMA

Rigdzin: Yes. And also, as I’ve polished my English, somehow I became an interpreter for many, many different visiting monks and a lot of political activists. For example, I translated for six or seven political prisoners, some of them are nuns who spent years in Chinese prison. They’re very, very sad stories.

Foremost, there was a one Tibetan monk, who was the most known in worldwide, Palden Gyatso. He wrote a book called Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk. So, I organized lectures at many places that I’d already been before with other Tibetan monks. So, I knew of sponsors in small, small outlets, so I called them and they’re all happy to receive Palden Gyatso and help him spread his words. He spent 33 years in Chinese prison.

During those times, people would ask what they could do for Tibet. I collected people’s addresses, then I went back to India, in my village, and put all these names in a hat. People would pick a name and then they would get a sponsor.

People would ask me, “Can you find me a sponsor?” One time, this lady came to me, crying, because her parents died, and she’s the oldest one in the family and they have other two kids. She asked if I could find her a sponsor so she could go to college, just a two-year college. I was able to find a sponsor for her. After many years, I got a call from Canada. The lady said, “Hey, Rigdzin do you remember me? You helped me go to college. I worked and I took care of my family. Now I’m in Canada!” This joy, right? Ha ha ha! It’s not me. Like you said, I’m a conduit. I don’t have money to give in my pocket.

DRK: Right, but you know how to connect people. How many time have you gone back and forth between the U.S. and India?

Rigdzin: At least eight times. I wish I could go every other year. I just love to see His Holiness. But I try to go whenever His Holiness gives a major teaching, for like 10-15 days at a time. I’d love to go to Dharamshala again, and maybe one more Tibetan New Year! Ha ha ha!

DRK: What year were you born?

Rigdzin: Two years before we escaped the invasion in 1959, I was born in 1957.

Also, as a child, I remember—you said the role, right. Even when I was young, a lot of people would come to ask me about something they could not find, if they lost a cow. I don’t know why they would. Tibetans have a cultural belief, that kids are innocent and pure and know things adults don’t. So, they ask kids questions. So, in that way, I was a little bit like an adult when I was like six or seven years old. I remember one time in our dormitory some kids lost something. Somebody stole it they thought. So as a kid they were asking me. And I said, “Okay, we have to do three prostrations to the picture of Buddha.” And then I said you have to be honest and if you’re not honest, you are going to shit in front of us. And as we did one kid literally shat, I still remember! He acknowledged he took it. So that things like that, see?

What I’m saying is, it is part of our culture. Then after many years in 2007, 48 years in exile for me, I knew I had a sister who is the oldest. My dad told me, when I was born, my sister was 24-25 years old. So, she would remember everything. I always wanted to go to Tibet and find her. And finally, I found her. I was able to meet my sister and she told me where I was born, and who gave me the name, right. So, so exciting! All this lifetime, I didn’t know. I just wanted to see what kind of place I might have been born. Right. So, when I was in Olympia, the newspaper people asked, “Where were you born?” I’d say, “In Tibet.” They would say, “Where in Tibet?” I’d say, “I don’t know, in a cave!” Ha ha ha!

Anyway, in 2007, my sister said, “When you were a kid, whatever you said would come true.” I said, “What do you mean?” She said, that when the Chinese started coming, you said that our uncle would be killed. She told me that I said my uncle would be killed and we would all go far away to live in a tent and not return. She told me I said that, and it all came true. Maybe that is the reason I became an interpreter because I could know things like that.

DRK: An interpreter is a conduit of languages between people.

Rigdzin: My father, and my ancestors, they were all healers. But also, it’s not just my family, the entire Tibetan people are like Native Americans. Especially like, two, three hundred years ago there were a lot of shamanic rituals, and all mountains are sacred, all rivers are sacred, like that. In my village, when I went in 2007, each household has a spirit. And they pray every morning. That’s very shamanic.

DRK: In Tibet, there was the shamanic culture, and then the Hindu culture, and then the Buddhist culture. And all three came together.

Rigdzin: Yes, yes. For Tibet, our earliest religion was called Bon, Bon was all shamanic. And yes, it has the Hindu, and within the Hindu there are many different Hindus right? With us, we are those who pray to snakes in the rivers, who are Naga. Similar like that, like in Kathmandu, all over the backs of the Himalaya there’s a lot of shamans.

DRK: Like Mount Kailash?

Rigdzin: Yes, Kailash was very close to our village, when I went, I could see in the distance Mount Kailash.

DRK: So, you were able to go to Tibet for the first time in 2007?

Rigdzin: First time and last time. It was just before the Olympics, and it was little bit scary because the Chinese asked lots of questions at each checkpoint. I was an interpreter for political activists and it was the same thing that they asked, each check point, if we were political activists. I was getting scared. But luckily, I was smart. I had a gentleman from Seattle, and he’s a big guy like you, and he was with me. They said, “Who is he?” I said he is my brother-in-law. Ha ha ha! He dressed more like military color and his hair was short. I was more confident because he is right next to me. So, I was not that scared. Otherwise, in Tibet, people disappear overnight.

How many Tibetans, for example, have been put in prison overnight? Recently I saw, they’re building a dam, they build many of them, but now what they’re building is a hydraulic dam in the most sacred and important river, the Yangtze River. And what do the monks do? We don’t believe in killing others. So many Tibetans, like 100, and monks, over 30, they self-immolated.

Dalai Lama’s guidance, you know, is about just expressing our pain without causing pain to other. And now, these monks and nuns, the entire village, great monks, great masters, they’re touching the feet of Chinese officers, begging them, please don’t build the dam. They’re begging them, crying the entire village coming like this, “Please don’t do this. That’s all we have.”

So, sometimes I get really mad about international, powerful countries always talking about peace, peace, but people who are walking the peace and talking the peace are left behind. Until people who can terrorize them, then they get attention. So, it is very, very sad and appalling.

In Tibet, if you are born there, you can’t say you were born in Tibet, you have to say you were born in China. When a paper interviews me, when they ask where I was born, they say they can’t write Tibet. I tell them, “I’d rather you write India than China.” That is how unfair it is, not only by force was Tibet taken, but then international communities still fail even to write the name, “Tibet,” on piece of paper. That’s my right. As a human being where I was born, I was born in Tibet. “No, no,” they say, “you should write China.”

So, this is how we give in to bullies and guns. You know, at the gun point they ask who you are. I say, “I’m human.” But no, no, they say, “Say you are a cat!” That’s how we feel right? When we say I’m born in Tibet, but no, we can’t we have to say “China.” That is sometimes very painful.

As a Buddhist, someday, I think maybe those Chinese people, the lucky ones, may be born into a Tibetan family. I know that sounds completely bizarre. But I’m saying, whenever we harm, it is putting a green light to continuous harming each other on earth. You know, we—each individual—you can say it is government, but the government is built by individuals, right? In order to become peace, individually, we really have to understand at a deep level that we are all the same. Whenever we get into the rigidity of me versus you—I’m better, you’re black, you’re white, you’re Asian, you’re Chinese—you’re my enemy. It’s really sad, right? If we really meditatively become open-minded, friends become enemies, and enemies become friend. Same thing in a bigger picture, if the world is one family, we are just burning ourselves.

There will be no end to the war. Sorry, it’s very depressing. But again, being taught about Buddha nature, and immaculateness of our innate mind, if we all really think deeply, it is possible. Like His Holiness says, “One human, one Earth.” We can live more harmoniously and happier and have more luxury than killing each other. It takes more time, more effort to kill and to destroy, then do live as it is. Just, just be, be patient, be respectful of each other.

Everywhere. We are just blaming each other, even the temples, the school shootings. I’m not just talking about America—everywhere—in some part of the world, blaming each other racially, you’re this party, you’re that party. Both are similar people within the country, but now people focus on division. And now this is scary in America, and the world, right?

DRK: With Tibet, from the exile in 1959, it doesn’t seem like it’s any closer to resolution. It doesn’t seem like we are getting closer to peace in the world, instead it seems like we are getting further from peace. The Dalai Lama has done a lot of good work for peace in the world, but it’s sad that Tibet itself is very, very locked down.

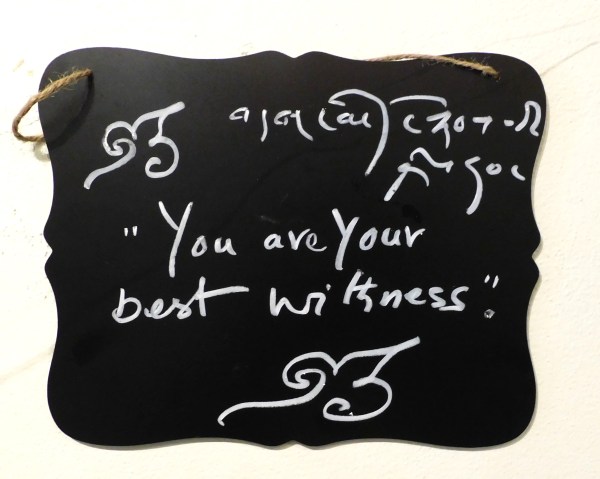

Rigdzin: Yes, yes, very sad. Like I said, in the middle of night, 1 AM, 2 AM, your husband is gone, and nowhere to be found. And many years later, you learn, he was in prison and now he is dead. The dead bodies that’s all you can visit, it is very sad. But also, I’m sometimes more sad for Chinese officers who do that. They also have a family. Eventually, we have to look into our own eyes. We are our best witness. What did you do, right? What do you do wrong? We always say, “You are your best witness.” And, and there are many stories of the Chinese, that they are very sympathetic, that they’re completely lost in pain, coming in the middle of night to the Tibetan masters and asking for guidance.

DRK: Because they lose their humanity.

Rigdzin: Yes, they think they did it to Tibet, but the same thing happens to them. Somehow, human beings need to set a higher standard, like love, forgiving, equality. One person’s power is very dangerous. We have a saying, one person’s smartness is less than three mediocre people’s decision. The collective decision is better than one person’s decision. We always say that doesn’t matter how smart the individual is, the collective decision is better for everybody.

DRK: There’s the idea of engaged Buddhism, of religion or spiritual practice that is also a type of activism in the world. Thich Nhat Hanh, spoke of that, coming out of Vietnam. In what ways do you see Tibetan Buddhism, and your own life, as not a spiritual retreat from the world, but an engagement with the world.

Rigdzi: One hundred percent. Yes, one hundred percent. I think, of course, His Holiness Dalai Lama, and most Tibetan, for example, monks and nuns, begging to the Chinese officers and touching their shoes. They could have punched them. But those are examples of peace. You want peace, you want compassion, you want non-violence? They’re the examples. And it might take a long time. I really think that no, territory lasts forever. If you look, the Roman Empire, Hitler all gone. Soviet Union fell, right? So, change is imminent. A lot of Chinese are actually reclaiming their ancestors’ faith, which is Buddhism. So, China keeping Tibet is actually an asset for China and for the world. I sometimes say that Dalai Lama is begging China, okay, you can take Tibet as a part of China, but give us legitimate rights under your constitution, minority rights, religious rights, cultural practice, right? That’s all he’s asking. And if they give that to the Dalai Lama, and invite him back to Tibet, I think China will not become weaker, they will become more powerful. They will benefit from Tibet. But, Tibet will also contribute to the world as an example of non-violence and peace and harmony.

My dad, at that time, was very poor, in India. He talked a lot about Tibet having gold. I said, “Where is your gold, I am sick and tired of sitting in this tent!” And you know what he said? He said, “Oh, by the way, we don’t believe in digging for gold.” I said, “Why?” He said, “We are nomads, we’re farmers but also not only that, we are human beings. If you disturb mountains and rivers, the animals will suffer, whatever they eat will have a less nutrition.” That’s what he said. And now I think that is a big social ecology. But he didn’t have those fancy words. He was just saying, what do you drink, the vegetables you eat, and the sheep there, the grass they eat. Is it undisturbed? If the minerals are there, it has more nutrition. He said drinking milk in India, or drinking plain water in Tibet—the Tibetan water was more nutritious. That’s what he used to tell me.

Then I asked my father, “What do you miss the most about Tibet?” What they missed the most is the water of Tibet. When I went, I saw it coming right out of the glacier from the rock. It’s like a pain in your teeth—so, so cold—chilling—and oh so sweet. And now what China is doing, in my village, that same water they are bottling, without any blessing, they named it Tibetan Miracle Water. So, if you empty out all the rivers and all the water, then the largest population in the world, all of Asia will suffer. And also, there will be more earthquakes, because when you make dams like that, it changes the balance of the Earth.

TANTRA

DRK: Speaking of balance, what can you say about tantra?

Rigdzin: Tantra, I don’t know a lot, but yes, those are higher Buddhist view. In the ordinary view, we say this world is samsara. But, in tantra samsara is nirvana. Right? Samsara means that the world is contaminated, that it is delusion. Literally it means you are caught doing the same mistake over and over again—chaos, delusion, desire. Nirvana, that is the opposite, it means peace, equanimity. In tantra, one thing and its opposite can be seen as the same.

In tantra, you have to have a pure perception. Pure view means all sounds are mantras, Even if somebody says, “I hate you.” That sound is a mantra. All human beings are enlightened seeing things as pure. It is called Pure perception. So, then it is breaking into nondualism. So, there’s no dirty and clean. So having said that, we don’t teach tantra immediately because it can be misunderstood and someone thinks, okay, then you can kill a person. But as sometimes I say, clean and dirty, is a kind of superstition. It also means you’re stuck, it is a fixation on dualism. Tantra is about non-fixation, right? So, for example, sometimes this is a bad example. But when you make love, you put your mouth everywhere, whatever the sanitation is. But then in a restaurant you complain about a little bit of fingerprint on the glass and say it is a “dirty” glass.

So, tantra is like that, in some sense. I’m not talking about the sexual, but I’m, just reaching for an example, so the Western mind can understand.

Tantra is often not good to talk about because of the complexity. Sometimes we are just like kids, first you have to crawl, and then you start running, and then not only you start running, now you’re jumping in the air, leaping and you don’t get hurt, right? But the infant, if you throw in the air, they will get killed or die, right? So, if the tantra is heard at the right time, by the right person, it can be very profound. It is quick sweeping, like a highway, and makes faster awakening. But, without true understanding, it can be faster disaster. Ha ha ha!

Tantra, when done with the right kind of craziness does not create a mess in life. Actions have to be done with a kind of love, so that even if something is painful, it can still be nirvana.

DRK: In many religions, East and West, there seems like there’s often a focus on transcendence, moving from this world to some transcendent realm. Then there’s imminence, where the Divine comes down and infuses this world. And it seems like tantra focuses on both at the same time. It is not about getting away from this world, or beyond this world. And it’s not that the Divine is only in this world. It seems like there is a focus on imminence and transcendence at the same time—nonduality.

Rigdzin: 100% Yeah.

DRK: And the Native American and Indigenous religions they seem to have a very immanent focus, that the Divine is not separate from everything here—like you said about the Bon religion and the Nagas, it is in the water, the mountains, and all of life.

Rigdzin: So, that’s why most Buddhism has said that samsara is nirvana. In classic Buddhism, we divide into six different realms and some realms are unpleasant, like hell realm, hungry ghost realm. But my own interpretation is like in a chart where hell is equal to anger. When anger consumes, you create hell right now. Lust and greed create the hungry ghost realm, right now in the present. Extreme pride, ego is god realm. We can look at upper realms and lower realms as something out there, but we can experience, here, the whole six realms in one day. That’s why samsara and nirvana are right here, right now.

Do you have any more questions?

DRK: Yes, what about the concept of samvega that I asked you about earlier? That idea of experiencing dissatisfaction coupled with the desire to grow?

Rigdzin: Samvega, in my own interpretation, is, like, energy. You become fed up with the insubstantialness of our modern activities. Sometimes in Buddhism, we call it “wrong view,” wrong view will always lead you to pain and suffering. So, samvega, on other hand, is the conviction to break through this childishness.

Like, you said here, medical workers, they’re burnt out. But not all of them are burnout, right? It depends on how one looks at things. With samvega, you can tap into that energy, so that I at least have an opportunity to help. Sometimes you have to take the Buddha’s way of looking at tonglen or exchanging suffering and compassion. What if you are that sick person? That’s an even worse situation. Like if a sick person was dying. Would you rather die, or would you want to do anything? Like, sometimes, in my own experience, when I’m really sick, I wish I could just wash the dishes—that would be luxurious!

Sometimes you also get sick and you might suffer, but still, you are there voluntarily, and, also, fortunately helping the other. Right now, in this world, there are others who are doing similar service, but in freezing cold weather, and with not enough food to eat. But here, at least in America, you have a heater, you have hot running water, cold water, air conditioning, and a large dining room, and plus you get paid. I’m saying it’s always a matter of perspective. Perspective is a switch on and off our mind.

So yeah, we all need samvega, because now here’s a story. When I was the interpreter for Palden Gyatso, he said he got beaten every day. And sometimes they would hang him from the ceiling, and they put fire underneath him, like almost live barbecuing human being, but they burn enough to peel the skin, but not die, and then they beat him. And he said he used to think at the time, to overcome the pain and madness, of the 18th hell-ish realm, where the person who is punishing you, or burning you, or beating you, they don’t ever get tired in the hell realm. But, here, in this realm, the person beating me will definitely get tired in half an hour, then I will have some break. And then also, when he would get extremely mad at the person, he would think, if he doesn’t beat me, he’ll be beaten by the authority. So, that’s how he survived 33 years of torture, and when he came out, he was still sharp and razor clear in his mind. Not only that, other monks, including himself, when His Holiness gave them an audience and asked, “What was the scariest part?” And Garchen Rinpoche, whose life I know, he said, the scariest part was he was losing his vow of compassion to the enemy. So, these are some things we should cherish as human beings in this world instead of ignoring them and disregarding them. These are the pillars of path to peace.

TEACHING COMPASSION

DRK: How do you teach that kind of perspective? How do you teach compassion like that?

Rigdzin: The biggest issue is you have to always exchange places. Like, in the West, you say you have to put yourself in another’s shoes. In every aspect, not just torture, not just politics, even lust. They’re being taught as a monastic, that you have to think this is someone’s mother, someone’s sister, like that, right. And even that cannot sometimes put a stop to one’s own mind. So, you might have to analyze, if you imagine taking the skin off a person, they will be not desirable, right? If you look into the stomach, it’s not desirable. So of course, it’s very easy to say, but I’m saying, in every respect, we have some sort of exchange, equilibrium, and exchange oneself for the other.

Like if the Chinese person, whoever was beating Palden Gyatso, were to think for a moment, “What if I was that monk?” If even for a moment you have this genuine thought, you will be little bit hesitant to raise your hand. It is completely mad to see just yourself and not the other.

DRK: So, one way of teaching compassion is to exchange positions, to take somebody else’s perspective. You also talked about analytical meditation and meditating on death.

Rigdzin: With tonglen practice, sometimes you have to give all your merit, love, compassion, everything to the adversary and take all their pain and misunderstanding to yourself in visualization.

DRK: I think about what the heart does. For medical people, we know that the heart accepts the used-up blood, the blood that the oxygen has been taken out of, and the heart accepts it, and then the heart gives it away to the lungs. And then the lungs give the heart the richest blood, the most oxygenated blood, and then the heart accepts it, and then gives it away. So, the heart is this organ of giving and receiving and the organ of transformation of accepting both the bad and the good equally and giving them both away

Rigdzin: When you do this, when you exchange and take on other people’s pain, some people are able to but do this will not affect them. But at that time, when you do that, in my own experiences, when you do that, when it is a suffocating situation, disheartening, complete madness, it immediately gives a path, some kind of space. That’s my own experience. That’s why I’m saying our mind is limitless. It has no shape, no color.

When we talked about before tantra, Buddhists call, kha dhak [kadag], primordial perfection. We are all born with that, it never depreciates, it never needs any addition. It’s already there. The only thing is that we love to be deluding ourselves. We have the habit of falling into self-deception of samsara through our self-cherishing.

So how do you get a different vision in life? You have to act like a great meditator, even if you are not a great meditator, because you want to create that habit of exchanging oneself for another, taking everybody’s pain to yourself. Just like acting and then someday you realize that you’ve developed the habit. So, when somebody says, “Hey, I hate you,” you are more prepared to say oh, it’s just a word. He may be mad at someone else, maybe his coworker but he’s shouting at me.

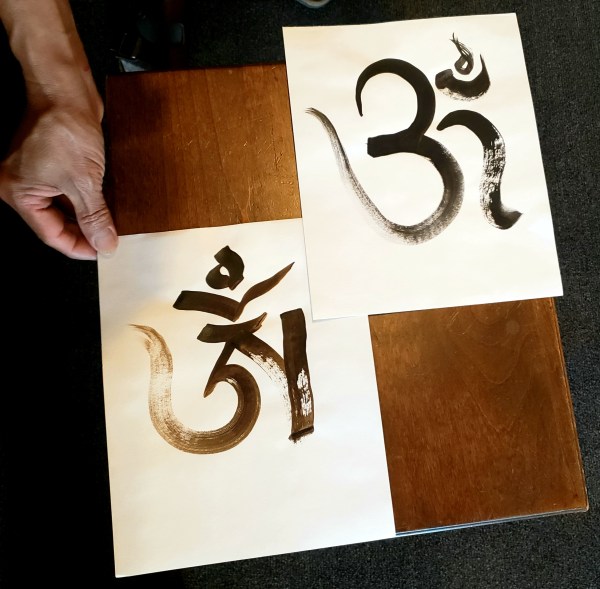

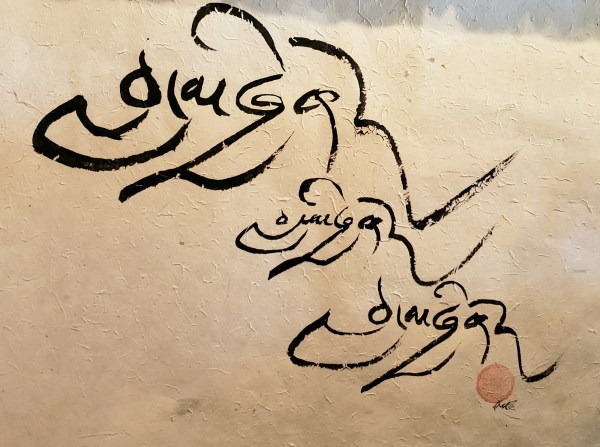

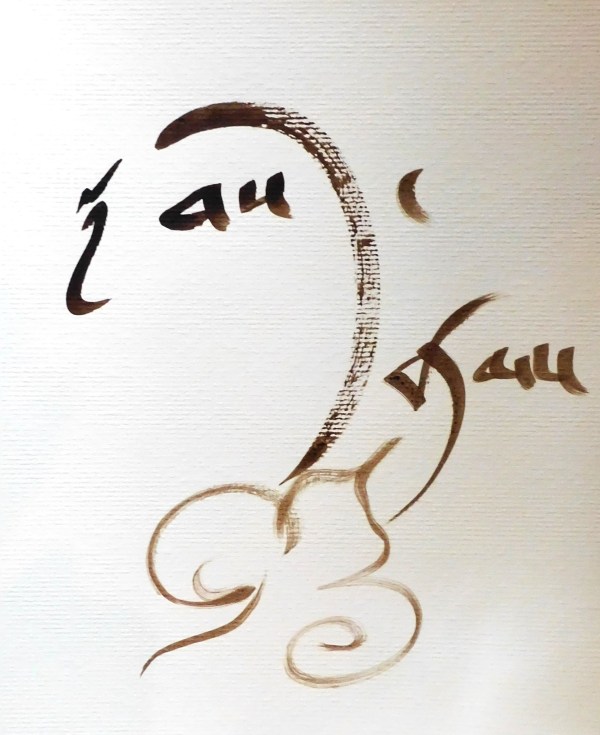

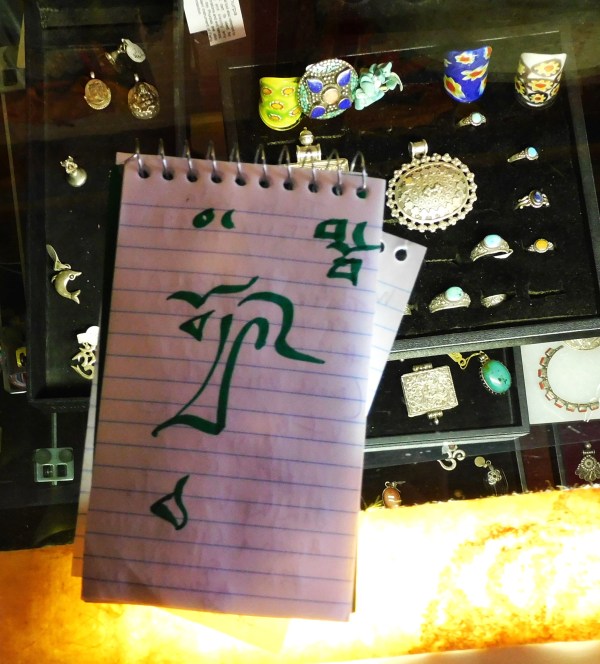

BECOMING AN ARTIST

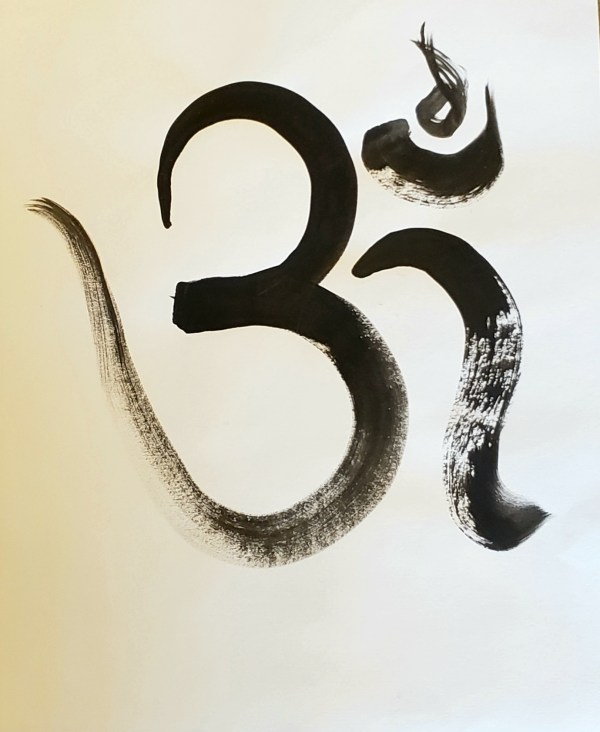

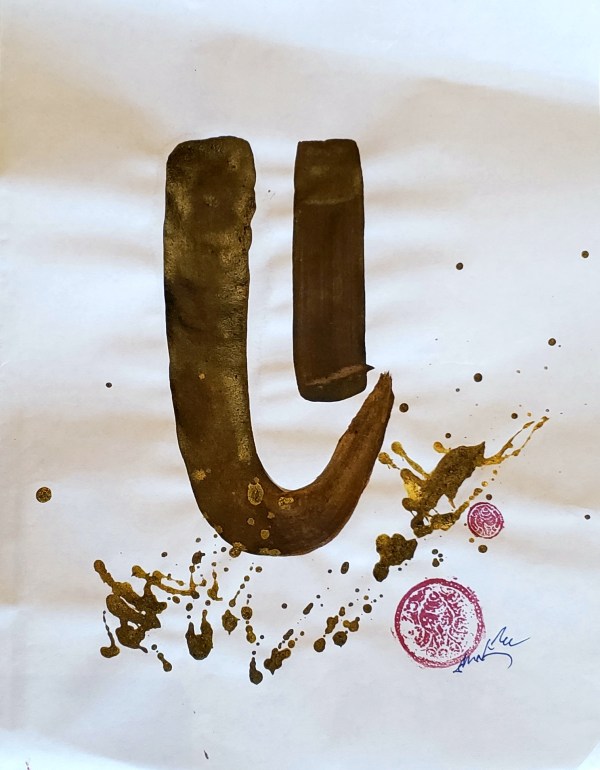

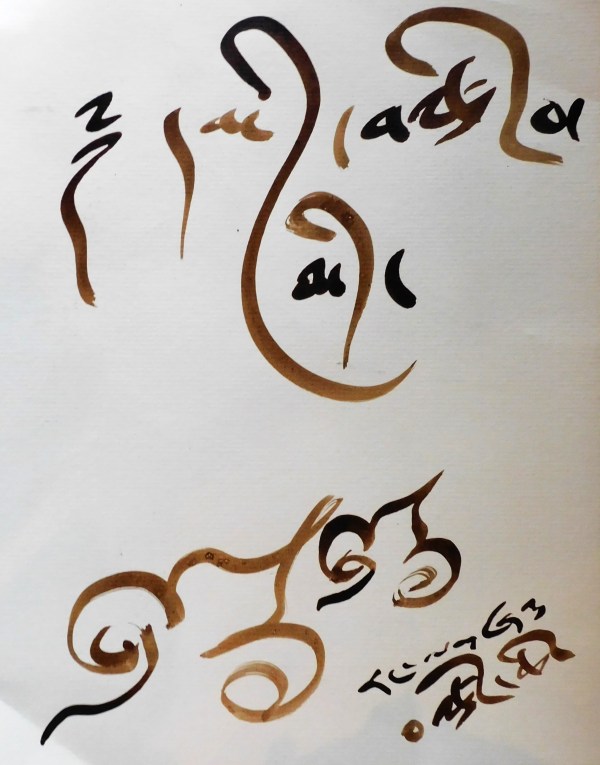

DRK: Let’s talk about art. When did you first think of yourself as an artist? What is the relationship between art and peace?

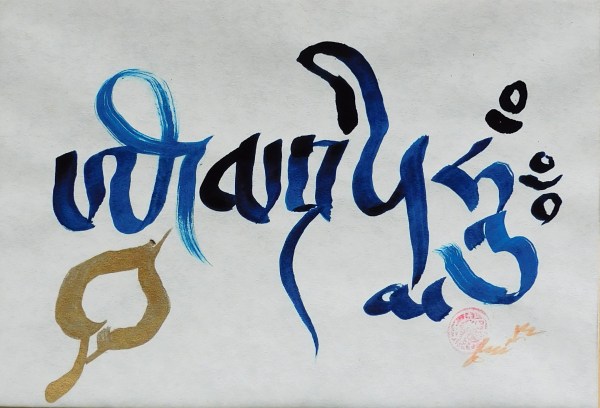

Rigdzin: I thought of art, at that time in childhood, as painting and coloring. I was having a hard time learning in school, especially different languages, like Hindi and English. And now I look at it, I actually have dyslexia. I see letters and numbers reversed. So, I always used to draw. Also it helped me with hunger. I get calmed down when I paint. I used to paint a lot of mountains and rivers. Maybe, in the back of my mind, I was missing those mountains and rivers, and tents and yak. That’s how my beginning was in art, but nowadays I do calligraphy.

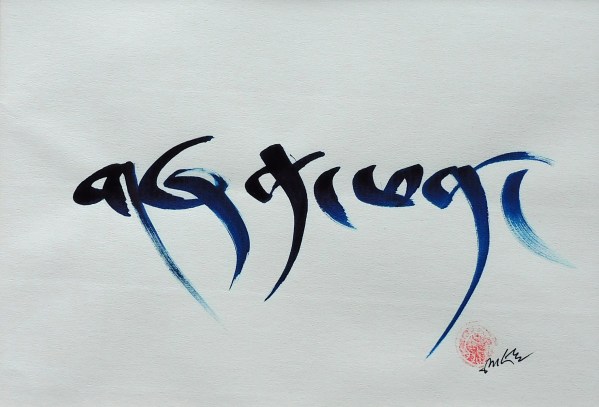

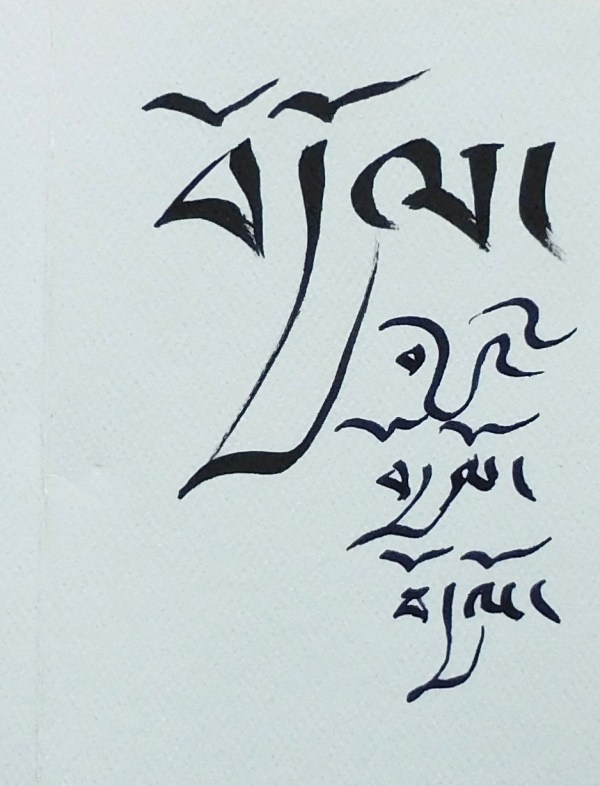

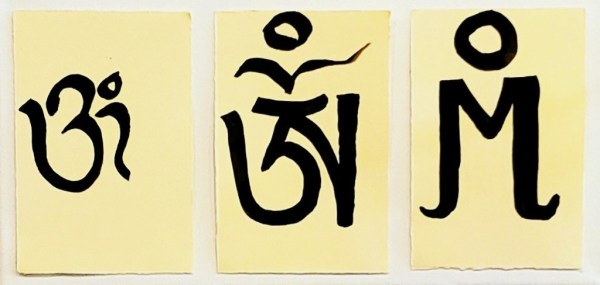

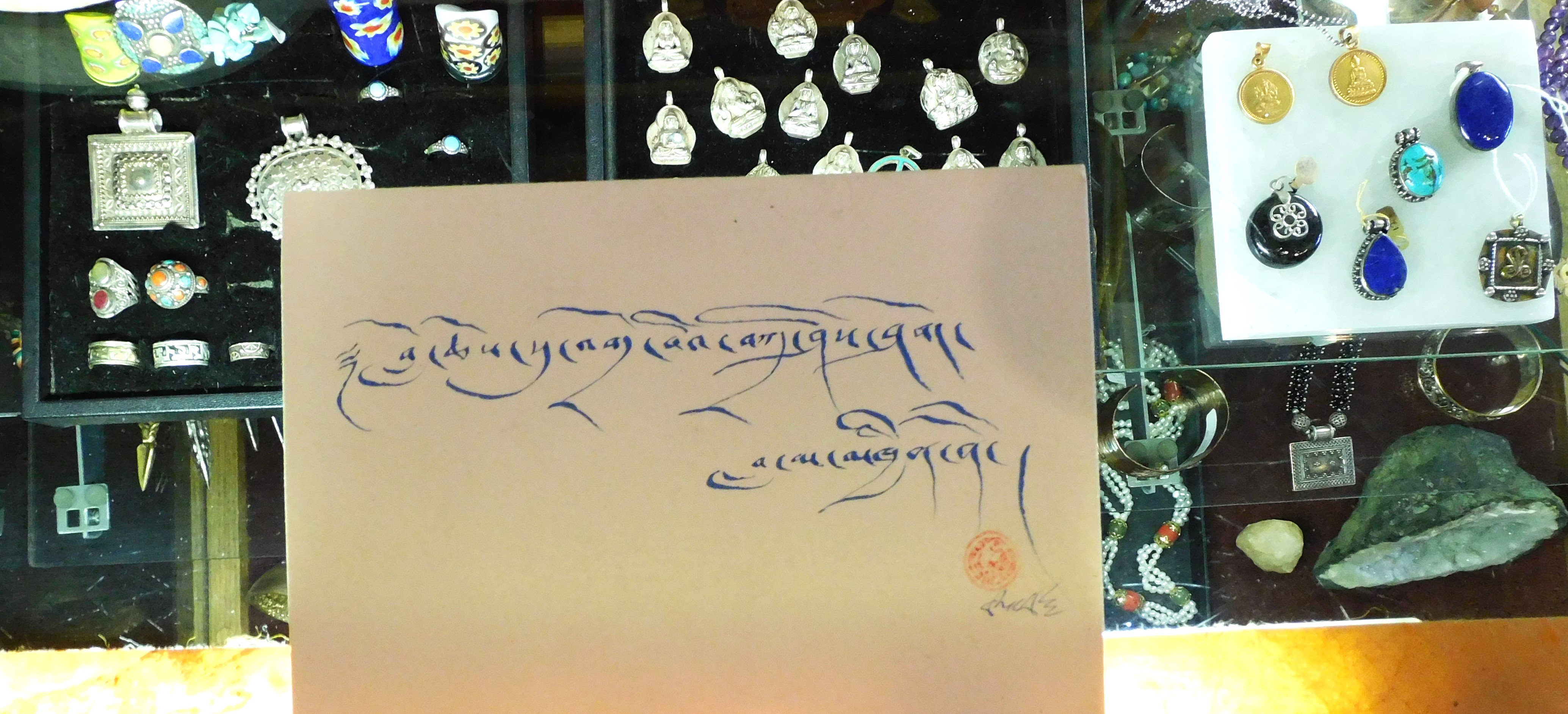

When I was very young, in Dharamshala, when first at school, we didn’t have paper because we couldn’t afford it. So, we had to go to the jungle and cut wood. But sometimes we couldn’t even find wood properly. So, I remember sometimes we find bamboo bark. It’s very easy to clean. And then, the monks at that time, our teachers are all old monastery professors. But they are homeless. We are homeless—refugees. Yeah, so they’re our kindergarten teachers. So, they taught in old Tibetan monastic style. So, we had to bring any kind of flat slate or wood. Then, we’d go to our kitchen and and make a paste with the ashes and put on a slate. Actually, now I look back, and we made “dry erase,” but it was organic. And then monks will go and cut bamboo and flatten it. Then they teach alphabet, Tibetan alphabet, like a, b, c, d. So, then I learned to be really creative. In Tibetan, I write pretty well, compared to a lot of people. In Tibetan, we have three different styles of writing. One is newspaper writing, another one is big letter, and one is fast writing. So, sometimes I combine three in one in my calligraphy. So, it becomes very interesting. It will take a little while to read, but those who are good high school graduates, they can eventually figure out what that means. My calligraphy teaches about the Dharma in condensed form.

I think the Tibetan alphabet is one of the best languages to explore Buddha, Dharma, and the nature of the mind. Science researches the brain, but what about the mind? Tibetan culture and language has explored the mind and consciousness.

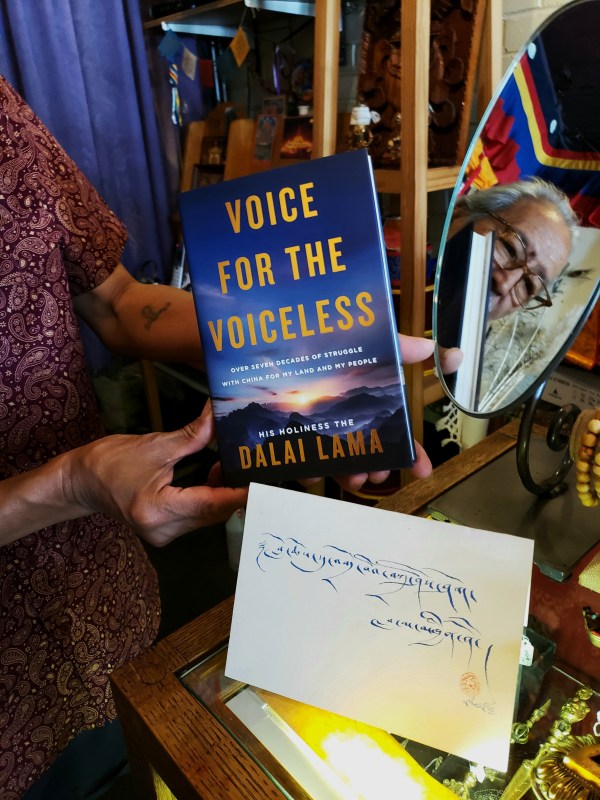

To end, I would like to speak about China. China has called the Dalai Lama a “wolf in monk’s robes.” They want the power and authority to choose the next, the 15th Dalai Lama, but His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama has said that Dalai Lama will be born outside of China, in the West. He has said that if the Chinese really believe in reincarnation, they should be trying to find Chairman Mao’s reincarnation and leave the Dalai Lama to Tibetans. In his latest book, Voice for the Voiceless: Over Seven Decades of Struggle with China for My Land and My People, Dalai Lama says that the next Dalai Lama will be born outside of China as long as China occupies Tibet. Padmasabhava said in the 8th century that when the iron bird flies and the horses run on wheels, the teachings will leave Tibet and go to other lands and the Dharma will go to the land of the Red Men.

The ultimate teachings of Tibetan Buddhism are for achieving Naked Mind, pure consciousness for experiencing non-dualism. The teachings are that you should see the other as yourself, you should develop compassion for the other, that you should practice Samantabhadra to develop Universal Good for all sentient beings. Chöeying is the meaning of the innate nature of mind to experience dharmakaya, the ultimate body of truth. But really, it is simple, love everyone and every sentient being, exchange places with others to understand their suffering, and have compassion for everyone.